Week Eleven

Genetics & Growth

Who does your baby take after? By now you might be seeing similarities with their maternal or paternal family members. Their grandfather’s chin. Maternal aunts eye shape. Genetics connect people across the generations and grandmothers love to dig out baby photos and compare. It can be fun to see who your baby takes after.

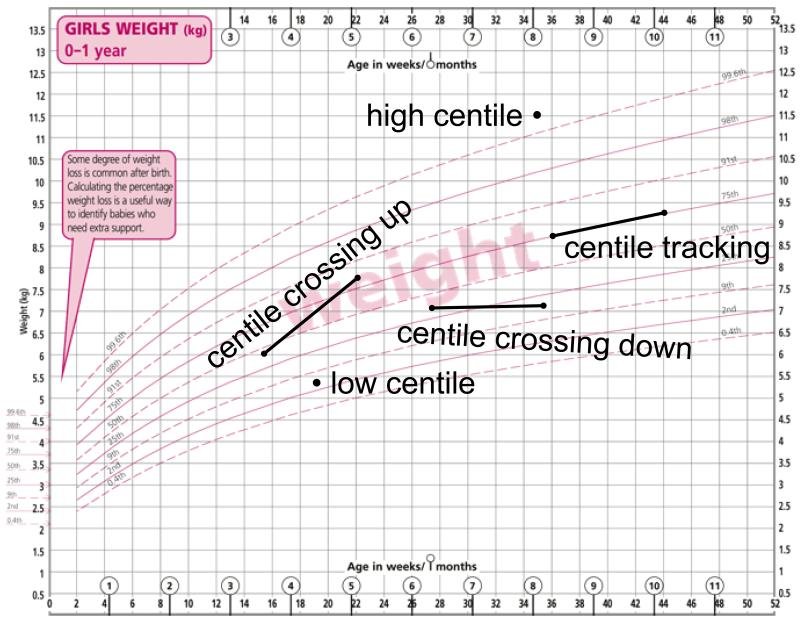

We don’t always think of these genetics when we observe our baby’s growth on the standard growth charts. At parents’ support groups it can feel like your child has been entered in the Biggest Baby Competition at the agricultural show and you aren’t taking home the blue ribbon. So it is really important to understand why we measure babies weight, length and head circumference and plot them on what we commonly know as growth charts.

The history of plotting children’s growth is fascinating. However, most relevant to the babies of the 21st century was a significant development early in the new millennium:

“WHO growth standard

An important milestone in international health occurred in 2006 with the publication of the World Health Organization child growth standard (WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group 2006). The study had a complex design involving infants and children from sites in six countries, selected to be free of constraints to growth and hence growing optimally.”

Dr William Sears describes babies natural body shapes as apples, pears or bananas. Along with all the other genetic factors we inherit, our metabolism type can also be inherited.

Long and lean babies - Sears calls them “banana babies” burn off calories faster than the plumper “apple babies” and “pear babies.” Banana-babies are likely to grow more quickly in height than weight, meaning they are often taller but lighter than anticipated. Babies with slower metabolic rates – apples and pears – can gain weight more quickly than height.

In five or six years, as you wave your baby off to their first day at school, you will see them amongst their peers and notice a huge variation in size and shape. Very rarely would anyone be particularly concerned by the difference in height or weight between this cohort born within a few months of each other. The tiniest student whose skirt reaches her ankles and looks like she might fit inside her enormous backpack is as developmentally typical and healthy as the wide-shouldered boy who towers beside her and looks like he belongs in one of the higher classes. These children have likely held these points on the charts for weight and height right from the beginning of life and if you look round at their proud parents and grandparents, you can identify who goes with who.

Your doctor or nurse is routinely measuring your child as part of a general health and development assessment. Variations on average are expected and you are not being assessed by how large or small your child is compared to their peers. Someone needs to be at the very edges of the charts and it is the progress they make along that pathway which matters.